A love letter to GETTING OLDER

“That’s great. You’ve got a lovely family, and I’m a goddamn amalgam!”

In the opening scene of Ron Howard’s 1989 film Parenthood, Gil Buckman (played by Steve Martin) reminisces about how each year, on his birthday, his father would take him to a baseball game, arriving late only to leave his son to be guarded by an usher. As the father leaves to see some ‘friends’, Gil Jr. enters into an increasingly surreal conversation with the usher, slowly letting the audience in on the joke. The usher is really a ‘goddamn amalgam’ of several different ushers from various points of memory and Gil Jr. is really the inner voice of Gil Sr. who has drifted off at some point in the ninth innings. Gil’s wife Karen breaks his trance -

“Game over, honey.”

The scene cuts to Gil, Karen and their sons traipsing back to the car, a perfectly average American family, Gil and Karen sharing knowing glances that communicate to the audience exactly what the movie will have to say for itself–parenting sure is hard, but everything’s going to be just fine. The distinctive voice and piano stylings of Randy Newman drift into the background and the title card appears in beautiful pastel above the family’s heads.

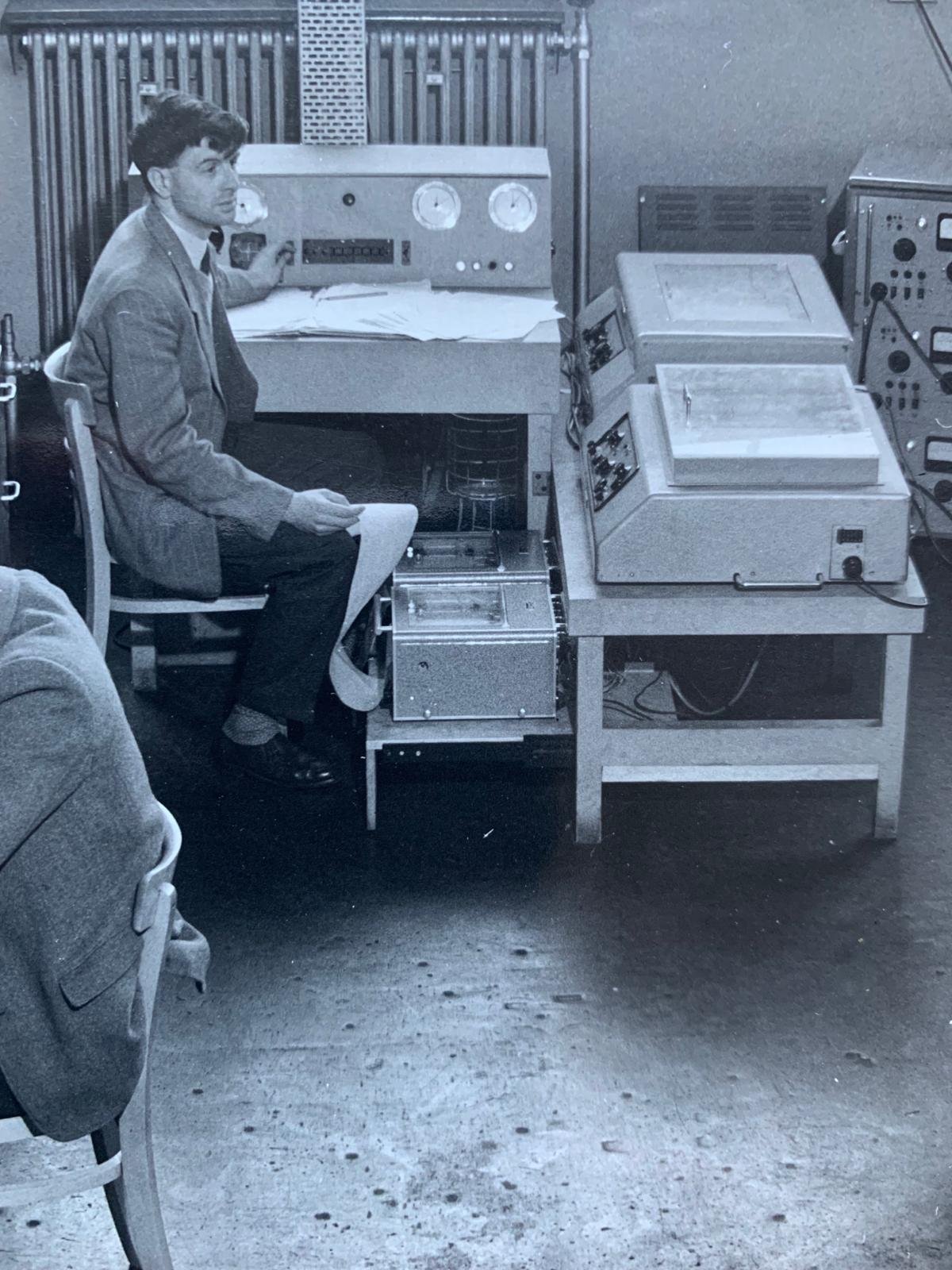

This scene has potentially more to say about my own stage in life than my grandfather's but that word ‘amalgam’ very much came to mind as we celebrated his 90th birthday on Saturday. As I stood with him looking at a selection of black and white photographs laid out on the kitchen counter, I asked him if it felt strange to look at them; him at an enormous computer recording the read-out of a flight simulator in Shorts; fifteen years later on a single-speed bike on a Mallorcan hill; forty-one years previously stood in his family garden in a baby’s bonnet; ten years later playing Snout the Tinker in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. ‘Yes, yes it is’ he replied, not needing to say anything more. The afternoon had been full of joyful noise and celebration of the life of a wonderful human being. Yet, it was impossible to look past the inevitable feeling of a eulogy being espoused about someone still very much alive.

Allow me a moment of introspection. As I approach my thirty-sixth birthday, I wonder if my grandfather ever felt the way I do now. I recently answered a text from my wife playfully asking what I thought my toxic trait was with the admission that I had never really considered the fact that I will inevitably die. Did that count? Call it the misplaced naivety of a youth spent within the clutches of neo-liberal individualism, mixed with a heavy dose of optimistic eschatology but, like Gary Johnston in Team America, my mindset could be summed up by the four words ‘I will never die.’ At the very most I unthinkingly entertained the notion that at some point around my centenary birthday, I would be tractor-beamed heavenward as I slept, like some post-modern Elijah. A ridiculous idea. The physical reality of my thirties has been anything but this, an extremely happy time but also a rude awakening and slow descent into middle age marked by a series of daft-punk-esque comparative adjectives; softer, slower, heavier, weaker. I imagine anyone reading this in their 40s and beyond chuckling at the depressing milestones I have yet to even consider, but for the first time I can feel the degradation of my body and it somehow manifests itself in deep physical disconnection and a paradoxical rootedness in its limits and ailments.

I’d wager that not many people want to consider the reality of middle age. Not the people leaving it to enter into their third act, nor the twenty and early-thirty somethings wandering into the maelstrom of endless bleary-eyed kingdom-building. And so I find myself daily fluctuating between making grand plans for the remainder of my allocated time and doing the exact opposite, acting as though I may be in its last days; taking two extra minutes at the start of every car journey to queue up the perfect song, stopping to look at the fleeting blossoms of Magnolia trees; opening the patio doors to listen to the wind blow through the garden at night; downing tools on a pressing piece of work to build a pillow fort with my boys.

Speaking of my children, they have almost preternaturally taken to their roles in this middling melodrama with gusto. They are in the slow, drawn-out process of finding out that their father is not the behemoth that they have spent Saturday mornings wrestling with, but is instead a physically average western male with (as they take great delight in telling me) plenty of poke-able ‘squidgy bits’. On a more intangible level, they rate every algorithmic suggestion made by my Spotify playlists on a very unscientific scale of nought to cheesy. The National are cheesy. The Walkmen are cheesy. The Notorious B.I.G. is cheesy. Very few songs score lower than a 5 on the cheese scale. The cultural tastes that I have taken three decades to hone and curate mean nothing to them. One of the few cultural touchpoints we have bonded over is the ubiquitous television show Bluey. If you don’t spend much time with children, you may not know the Heelers, a domesticated family of Australian dogs - mum Chilli, dad Bandit, and 2 sisters, Bingo and the nominal Bluey. Accepted wisdom within the parenting world is that Bluey is fabulous TV written for children but with an understandingly sympathetic wink and a nod to adults. The show has even spawned a right-wing rival, Chip Chilla, an American attempt to combat the Heeler’s morally-relative, hangover-admitting, Easter bunny-loving soft-nihilism. Unsurprisingly, it hasn’t registered on my children’s radar yet.

Bluey is indeed fabulous TV. I’ve used it on multiple occasions to teach my media classes about narrative structure and how to appeal to multiple audiences simultaneously. And yet Bluey’s dad, Bandit is problematic, at least for that most narcissistic of viewer, namely the human adult male. He is a crystal-clear embodiment of masculinity in one’s middle ages; he thinks he’s hilarious, athletic, admirable, an amorous and worthy spouse and despite some evidence in the affirmative, the show also tends to paint him as a figure of ridicule; a slightly more successful, more emotionally literate Homer Simpson. There is an ongoing trope, for instance, suggesting just how bad his shit stinks, literally. He gets food on his belly, is regularly schooled emotionally by his wife (but why are you teaching them to play chess?) and his competitiveness with his brother shows an arrested development that hits ever so close to home. His body often takes on a magical-realist guise; an unexplored hinterland for finger-puppets, for example. It is odd to identify that the most acutely realised representation I see around me of myself is a smelly if affable, blue cartoon dog.

And yet Bandit exemplifies the one human trait that is perhaps more admirable than any other, the choice to face life’s ups and downs with a dogged determination to create meaning where there could easily be nothing or, worse, despair. The low points in Bandit’s life are emblematic of the ‘first-world problems’ that we perhaps dismiss emotionally, due to their supposed banality; changing jobs or moving house but two moments in the most recent slew of long-awaited Bluey episodes remedy this, underlining Bandit’s quiet everyman quality with pinpoint accuracy. In the first, ‘Stickbird’, Bandit ends the episode by silently engaging in a mindfulness exercise taught to him by his daughters–miming the removal of his worries from his belly and his heart before throwing them into the sea. The relief from whatever existential anxiety he had been enduring is palpable in a deep but quiet sigh. In the second, ‘The Sign’ (spoiler alert) Bandit makes a big Jerry-Maguire-esque play to wrestle back some control of his life and put his family first, wrenching the ‘for sale’ sign from the ground in front of his beloved family home, letting his wife and children know in an instant that they don’t have to move house after all. The dramatic irony in the fact that the viewer already knows that none of the characters really wanted to move away from their friends and family (having paid lip service to the ‘big adventure’) fills the scene with an almost unbearably euphoric pathos.

Throughout the episode, Bandit repeats that he just wants to give his family the best life that he can. By the conclusion, he has realised that ‘best’ can exist within the limitations and finality that life imposes on us all to one degree or another whether we want to admit to them or not. Which brings me back to my grandfather, one of the few people whose lives I have witnessed enter into a place of harmony and, from the outside looking in, true contentment. I know that at some point he will be forgotten, a link in a family tree that future generations know at best by name. And yet on Saturday, he was as alive as anyone I have ever known; jokingly reminiscing with his children, quizzing his grandchildren about their thoughts on generative AI, getting down on his hands and knees to play a beetle drive with his great-grandchildren. In those moments the churlishness of my mid-life concerns were squarely put in their place; the hair loss, the pudginess, the sense that all of this will have to come to an end someday.

In the Noah Baumbach film Greenberg, Ben Stiller plays the titular character, a cranky middle-aged man who has decided ‘to just do nothing for a while’ after trying and failing to become a professional musician. ‘That’s brave – at our age’ he is told by a female friend at a pool party. In one of the film’s episodes, Greenberg ends up at a house party, telling a room full of young people that he hopes he dies before he meets one of them in a job interview. And yet behind Greenberg’s apparent nihilism, there is a quiet hope; in freeing himself from the expectations of his earlier self, he manages to fall in love and begin to find himself. So perhaps there is a truth in Greenberg’s defiance of what we may culturally inherit as the idea of a life lived well. A truth mirroring that of Bandit Heeler’s, one that is inherent in the contentment that I see when I look at my grandfather; perhaps it is brave to do nothing; and perhaps ‘doing nothing’ isn’t really doing nothing at all.